America's Forgotten Statesman

The President who carried America into the 20th century has a lot to teach us about qualities particular to American leadership- and offers a blueprint for Donald Trump to follow

American partisan debate can be quite tiresome. In a sick bizzaro-world mirror of some ancient Greek Aristocracy; somehow the most idiotic, unaccomplished, and spiteful people are given first priority when discussing matters of politics— while intelligent, measured, humble, and gracious people are rhetorically pushed aside; regularly denounced for transgressions of the idiot orthodoxy (maybe I meant ancient Greek Democracy).

Normal Americans are castigated as racist, sexist, antisemitic, homophobic, and all the rest of that blather by mutant radicals espousing all sorts of murderous thoughts that boil down to one thought in particular, which is that to be normal is to be opposite the “good”— and that said “good” is merely liberal progressivism. Somehow, this commentary came to be the norm in the country started by men like George Washington, John Adams, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton; a rugged, serious, pragmatic, Christian country founded by aristocrats, businessmen, and warriors. To reflect on the fact that unserious people like Joe Biden and Kamala Harris are a representation of this great land called America is enough to hang one’s head in shame, and to send one swimming for answers in a sea of confusion.

“What happened to America? Where did it all go wrong?”

There are lots of varying answers to this question- some good, some poor, some in-between. Some very dumb and very stupid idiots who huff wet paint and gasoline for fun (in the style of the esteemed Richard Hanania) say that America was bad from the beginning (you should ignore these morons). Others say that America was a wonderful country until the Tyrant Lincoln decided to start a Civil War by being the most popular candidate in an American presidential election. Some others insist that either Woodrow Wilson, or FDR, or Lyndon B Johnson ran this country into the ground by being physical and/or mental cripples (opinions on Joseph Robinette Biden notwithstanding). Still others say that 9/11 deeply scarred the American psyche, positing that America has never been the same since the CIA blew up the Twin Towers. True Qatriots know that Barack Obama was actually the Mohammedan antichrist who ruined America by creating government healthcare and ISIS.

Obviously, I’m being a bit tongue-in-cheek, but you get the picture: lots of questions about the fall of America are always floating about nowadays. The trouble with questions, of course, is that they are supposed to lead to answers— though very often, they lead to more questions. The next question that pops into my mind is the thesis behind much that gets discussed on the Right, and I believe Donald Trump’s theme of “Make America Great Again” is a somewhat oblique reference to this question. In asking where the train ran off the tracks, the question is:

“When was America still America?”

There are several good and bad answers to this question, just the same as the last question. But in the annals of American history, there is one era— defined by one man— that showed us the last incredible gasp of institutional, cultural, and moral America, as intended by the men of the Founding. A time when America was still America…

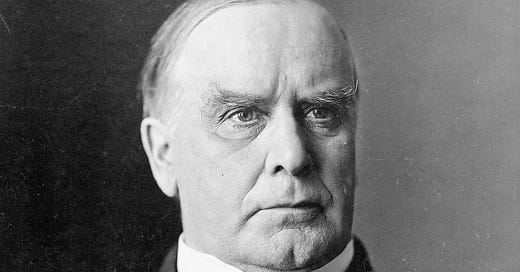

McKinley, the Man

On the morning of January 29th, 1843, the McKinley family welcomed William Jr. to their humble abode in Niles, Ohio. The son of a modest businessman in the steel industry, little William McKinley was hardly set up to be a Great Man— but the dice have a funny way of rolling.

As the young boy grew, he took a liking to his modest education- he grew up reading David Hume’s History of England, Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, the works of Charles Dickens, and of course, the Bible. As the boy became a man, he decided to enlist in war; specifically, the American Civil War. Young William showed great courage throughout the war, moving up through the ranks of the 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment, becoming a Brevet Major before the end of the war. “Major McKinley,” as he was then referred to for the rest of his life, decided to get married and enter into the law profession, studying under a local Ohio attorney. A few years later, he was co-partner at a successful law practice.

Most people at this point in their lives would probably settle down, lock into their career, have a couple kids, and rake in the dough. No one could’ve blamed McKinley for doing so; he provided for his family and made his parents proud, on top of being a veteran, all at the age of only 26. The Major was made out of the right stuff.

But, as it turned out, Major McKinley was made out of more than the right stuff: he had Providence behind him. He miraculously avoided any & all injury during the War effort (despite facing the Confederate Army multiple times in battle), and continued to win elections at the county and congressional level against Democratic gerrymandering and election rigging early on in his political career (hmm… sounds familiar…).

From the time he joined the Union Army as a young man until he was dying from a gunshot wound at 58, the Major never failed to miss a service at whatever Methodist Church he could attend, wherever he was in the United States. In the Inaugural Addresses for both of his terms, McKinley made sure to open and close his speeches with praise of Almighty God, asking the Lord to bless the country and his presidency. In 1897, he proclaimed, “Our faith teaches that there is no safer reliance than upon the God of our fathers, who has so singularly favored the American people in every national trial, and who will not forsake us so long as we obey His commandments and walk humbly in His footsteps,”1 and during his Second Inauguration, McKinley expressed his gratitude to God and the American people:

“[E]ntrusted by the people for a second time with the office of President, I enter upon its administration appreciating the great responsibilities which attach to this renewed honor and commission, promising unreserved devotion on my part to their faithful discharge and reverently invoking for my guidance the direction and favor of Almighty God.”2

McKinley’s natural ability (another sign of Providence’s favor) made an impression on everyone he met, friend and foe alike. Throughout his life, he was extolled as a man of virtue, a compelling speaker, a beacon of wisdom & warmth, and a quietly brilliant statesman. H. Wayne Morgan, a historian of the Gilded Age, said that McKinley’s popularity with the American public “eventually reached a level approached by no President in the nineteenth century except Andrew Jackson and perhaps Lincoln.”3

It was these characteristics that drew me to McKinley as I read more and more about him- I had been doing some academic research related to how Presidents interacted with their Congresses, and I had become interested for other reasons in the Spanish-American War. Needless to say, McKinley became the star of the show.

But McKinley’s character is not the sole reason I decided to dust off the ol’ typewriter and get to writing again. Much more importantly, McKinley’s policies and statesmanship offer us a blueprint for what America ought to (and can) be once more.

McKinley, the Politician

The policies of President McKinley cannot be understood without the proper context of late nineteenth century American politics. After the end of the Civil War in 1866, America’s most pressing issue was how to reconcile the South with the rest of the Union. The answer of the Congress under President Andrew Johnson and under the Grant administration was “Reconstruction,” a euphemism for the destruction of Southern society, looting the South of its resources and destroying any chance at rebuilding the South’s economy & culture. Understandably, this built up Southern bitterness toward the American ruling class in Washington DC, and toward the Republican Party as a whole— which enjoyed its position as the leading party for nearly half a century.

It was during this era of Republican success that McKinley learned the ropes, honing an impeccable political instinct that would inform one of the greatest Presidencies in American history. The President following Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, was McKinley’s commanding officer during the war, so McKinley used his connection to the President to navigate his first years in Congress. The Major made a name for himself in the Gold/Silver dollar backing debates, and emerged as an advocate for the tariff. As the years went on, McKinley went in and out of the Congresses under Presidents Garfield, Arthur, and Cleveland; building an incredible repertoire of political experience. As the 1888 campaign came around, McKinley expertly maneuvered himself into a position as one of the Republican Party’s greatest speakers and most honorable statesman, declining to put his name in the ring as a dark horse Presidential Candidate during the 1888 Republican National Convention, instead throwing his weight behind one of the two favorites, Senator Benjamin Harrison (the other, Senator John Sherman, failed to capitalize on his advantage during the first 7 party ballots). Harrison would go on to lose the popular vote marginally but win the Electoral College handily in the 1888 election.

It was during this time that McKinley ascended to the Ohio Governorship, having decided that there was little left to accomplish in the House, and much that could be lost. In 1891, McKinley ran a brilliant campaign for Ohio’s Governorship, beating the incumbent Democrat, James E. Campbell, by 20,000 votes. For the next four years, McKinley cemented himself nationally as a voice for American farmers and workers, often breaking with Republican Party leaders and with wealthy corporate interests— although McKinley was neither a man of only the wealthy or only the downtrodden. Instead, he was a man of the high, low, and middle; a “President of all the people.”4

There was only a slight problem in 1892. As McKinley soared, the Republican Party sank. Open rebellion in President Harrison’s cabinet (notably by former Presidential candidate, Secretary of State James G. Blaine, who eventually resigned) and dissatisfaction with the Party at large made the Republican Party seem impossibly weak in the lead-up to the 1892 Presidential Election. McKinley avoided dissension, but kept himself quiet on who he would support for President. He allowed rumors about himself as the nominee to grow, only to cut them down at the last moment in support of the incumbent President— during that year’s convention, McKinley presented no challenge to Harrison, despite massive cheering every time he spoke as the Party Chairman.

In the end, it was an incredibly savvy decision. Harrison would get demolished in a rematch with former Democrat President Grover Cleveland in 1892, and it appeared as if McKinley would have no serious challenger for the Republican nomination in 1896. This logic ultimately proved correct— McKinley cruised through his gubernatorial re-election, winning by over 80,000 votes in 1893; easily poised to become the Presidential nominee for the 1896 election. McKinley once more was an island of success in a sea of total failure.

President Cleveland, in the meantime, pursued an overturning of the previous Republican administration’s policies on the tariff (opting to be more free trade, overturning a tariff bill authored by McKinley) and on the Silver question (repealing the Sherman Silver Act), immediately creating a bank run— Americans feared that the Cleveland Administration’s new monetary policy would mean that they would need their savings immediately. Even worse, undoing the McKinley tariff allowed the US economy to get tangled with Europe’s economy, which at the time was floundering due to the Long Depression (thereby tying the US to a sinking ship).

The Panic of 1893, caused by ideologically-driven Democrat economic policy (there are no recent parallels to these circumstances whatsoever), hit the nation hard— and Ohio was no exception. Workers and Unions agitated in the streets at levels previously unseen. Poor Americans turned to insane political radicalism, falling into the clutches of Anarchy and Socialism. Immediately after his second inauguration as Governor, labor strikes broke out all across the state. The Major, who was personally friendly with many labor leaders, was faced with a brutal decision: play nice with labor, get them to dial it back a bit, and maybe still have a shot at higher office; or crush the riots for the sake of Ohio’s personal peace, at the likely cost of losing the Presidency.

Once again, William McKinley was thrust into an unenviable situation that would’ve made lesser men squirm. Most would’ve gone the route of acquiescence and tried to play nice with the rioting mobs, caring too much for their own political offices & reputations. Not so with the Major. In a letter to John McBride, the leader of the United Mine Workers (who were rioting in the streets), McKinley spared no time for effeminate pleading or veiled threats:

“John, you have gone too far. If you do not stop it before evening, I’ll order out the entire National Guard.”5

Short and sweet, the Major followed through. It worked. Although various other workers’ groups continued to cause trouble for the next two years, McKinley had a tight handle on street violence, making Ohio much safer than its neighbors during a very troubled time (so much so that McKinley was quietly asked to help moderate behind the scenes between labor protestors and the state government in Illinois).

By 1895, as the Panic began to subside and his governorship wound to a close, McKinley had forged a nationally renowned & highly respected reputation out of nothing. He was seen both as a champion of the downtrodden American suffering from depression and as an enforcer of law & order. He was seen by the public both as the ever-charitable gentleman and the fiery Scots-Irish speaker. He was a bridge between the rich & poor, but a barrier separating radicals from everyday Americans. Before he was even approached about the possibility of running for President, he had become a Statesman. The White House seemed inevitable.

It was.

McKinley had no realistic challengers at the June 1896 Republican convention, winning the nomination on the very first ballot (for context, the previous nomination that went to Benjamin Harrison, an incumbent President, took 8 ballots), and he picked a highly competent but still unproven Vice President named Garret Hobart. He campaigned hard, with no significant setbacks, preparing to face the upstart Democrat William Jennings Bryan in the Presidential election that fall. Bryan, a Congressman from Nebraska, was most famous for thundering, “You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold!”6 during a speech at the Democratic National Convention. He was a hardline supporter of a silver-backed dollar and the sharpest opponent of the Gold Standard, and he went so far as to seek support from the Populist Party— an incredibly radical agrarian political party born out of depression, and one of the last safe havens for “greenbackers,” who believed that the dollar should not be tied to any standard at all, and that its value should be determined by the US government (thank goodness no one would ever be crazy enough to put such a thing into practice).

William McKinley overcame both Bryan’s wild-eyed moralizing and some defecting Silver Republicans to win the 1896 Election by just over 600,000 votes, receiving 271 electoral votes to Bryan’s 176. Winning the Presidency was a massive accomplishment, but it would not be the end of the Major’s battles. My cheery summary of McKinley’s Ohio governorship may have tricked you into thinking that the United States was chugging along as per usual, but you would be mistaken. President Cleveland handed McKinley an America that was economically flailing, prone to political radicalism, losing its self-identity, and on the brink of war with a foreign power.

America, Great Men, and Our Future

Astute readers may notice that I have left them hanging on a cliff, much like Scar with Mufasa (except that I’m just verbose, not evil). I have spoken very little thus far about what events actually transpired during McKinley’s Presidency. For that, I apologize, as I feel the need to steal a bit more of your hard-earned free time first.

Some months ago, I became engulfed in a debate with Roland Gunn, a poster on Twitter who is one of the most astute chroniclers of what people, places, and cultural norms make America what it is (@RolandGunnTN is the account you must now follow). Most of the time I would be afraid to disagree with him too harshly— he is one of the few people I consider truly more American than myself— but in this case I thought he made an error in saying that “Franco/Caesar posting” is un-American and dishonors our American ancestors.

(I have attached the full exchange below:)

It is not so simple to say that America has a poor relationship with Great Men, simply because George Washington turned down the crown when he was given an opportunity to take it. Titles do not a Great Man make; rather, Men who are Great make Titles the same.

Contra Roland, the Great Man is a thoroughly American archetype. Americans are more than happy to gather themselves under a leadership of One— we have been more happy in eras where we were ruled by the unquestioned leader rather than by unaccountable oligarchs and weak pushovers. Better the highs and lows of Washington, Jackson, or FDR than the uncertain melancholy of Johnson, Harrison, or Biden.

When investigating the legacy of McKinley, this pattern once again manifested itself. McKinley was handed a seriously fragmented nation in decline, but left the nation in the best condition, maybe ever (many people have been saying so). Economically, McKinley ended the Panic of 1893 and replaced it with the Era of Confidence. He took the deeply embittered North/South tensions and left behind a unified America. He was handed an understaffed and underpaid military on the brink of war, and turned it into a quick 4-month curb stomping of a European imperial power. The Major came into office steering the wheel of an America pushed around by foreign powers and corporate interests, and made them all choose between stepping in line or getting their teeth kicked in. He found a nation of wood, blood, and grime and left it a nation of steel, gold, and marble.

But this was not what made McKinley truly a great man— it was his understanding that to lead something as vast and differentiated as a nation, a leader must become the symbol of the nation. To be the leader of a nation is to be the nation. Cartoonists in McKinley’s era understood this well: American and European cartoons switched from depicting US policies as being carried out by the figure of Uncle Sam, instead depicting McKinley & America as one and the same.

A small example: McKinley picked up smoking during his service in the Union Army, a habit which he did not break during the whole of his life (despite his wife’s disapproval— McKinley was also immune to the Longhouse). However, upon his decision to run for the Presidency, McKinley totally dropped all smoking in public. He remarked that it would not be right for the young men of America to see their President smoking.7 It was a small gesture, but a perfect illustration of McKinley’s understanding of the symbol of the leader.

Someone who wishes to lead must set the example for the ones who follow them. Christians have the best understanding of this archetype— “Imitate me, as I imitate Christ,” says the Apostle Paul. The Leader becomes the blueprint, a living instruction manual that says, “step here and not there. Listen to X and not Y. Go thus far and not a step further. Withhold your judgement for these here and bring justice to those over there.” A leader is there to fight the battles for those he leads, before they are even aware that such challenges lay ahead. To lead is not to be privileged above all others, but to empty oneself of one’s own desires, and to carry the weight for everyone else. To be a leader is to be selfless. America in particular presents a tremendous responsibility that causes one to shudder— 350 million or so souls hang in the balance. “Not many of you should become teachers, my brothers, for you know that we who teach will be judged with greater strictness.”8 So how have our leaders dealt with this heavy weight?

They are unwilling to even make a concession like McKinley with the cigar. Lauren Boebert gets touchy in a public movie theater with her boyfriend, while she was still married to another man. Paul Pelosi got up to who-knows-what with a hammer and a crackhead. Speaking of crackheads, we’ve all heard a thousand awful stories about Hunter Biden. The supposed President of the United States may or may not have taken bribes from foreign governments. None of our leaders feel the need to moderate their behavior, and none feel any moral responsibility to shepherd those who have been placed in their care. Elected officials in both parties take every opportunity to mock, deride, and persecute the backbone of the country- white evangelicals- and enrich themselves and their family members while claiming the title “public servant.” The depth of betrayal committed by American leaders cannot be overstated. They are fat, decadent, degenerate, arrogant, vicious losers who are embarrassed of the label “American.” They hate every symbol associated with America and its people— the flag, the statues, the Christianity, the quiet solitude and peaceableness that all normal Americans respect and wish to follow. Our leaders could not be more anti-American if they tried, even if they were 1950s Soviets.

This betrayal, luckily, has not gone unanswered. A single, solitary American stepped into the void to not only denounce our traitorous leadership class (which any random Joe can do), but to fight these losers. Donald Trump— not the Pro-Life movement, not Conservative talking heads, not Western thought leaders, not Right-wing think tanks, and certainly not you reading this— was the one to take up the mantle, to hold the banner of America, to charge into battle against these people who have destroyed our great country. From the moment he came down the elevator, Trump has lost friends, family, status, wealth, businesses, and his reputation. Even in the last year, he has been arrested and threatened with jail time, and had threats of freezing his assets from rogue partisans at the state and federal level. Worst, on July 13, he came within an inch of having his brains strewn about a stage at his rally in Butler, Pennsylvania. Almost no living American can claim to have sacrificed as much as Trump has for the cause of putting this great nation back together.

Trump’s call to “fight, fight, fight” was an expression of a great leader. He did it instinctually, with no prior coaching or prompting needed. Trump is best playing off script, not when taking cues from staffers or advisors.

I had delayed in publishing this article because I didn’t quite know how to finish it— I wanted to ask, “how is McKinley relevant to today?” Well, his policies are great, sure. But it doesn’t capture what I wanted to convey about the man. But when the Very Failed Assassination happened, I figured it out: Trump has an opportunity to take up McKinley’s mantle as the leader of America, not only in title but in practice.

In the years after McKinley’s tragic death (at the hands of an anarchist immigrant) America exited its most prosperous years. Taft and Wilson cranked up immigration, the US Government decided to “make the world safe for democracy” instead of ruling its own people, and fruitless wars destroyed our culture’s social cohesion. Rank degeneracy and social upheaval followed throughout the rest of the 20th century, and those fruitless wars were now not even declared legally; showing that our ruling class had totally checked out of all pretense of responsibility to the American people. This reality dawned on Americans, and they picked various champions to represent their cause- Nixon, Reagan, Bush- but all failed or betrayed their promises to put America back together, being shoved out of power or else captured by it. “The Era of Confidence” died with McKinley, and no American statesman has been confident, competent, intelligent, or ruthless enough to restore it since. When I asked, “when was America still America,” the answer clearly shown is now “when America was McKinley’s America.”

Now, once again, Americans have chosen a champion to restore American greatness. The real appeal behind Donald Trump was always that brilliant slogan, Make America Great Again. It is a call to return to McKinley’s America: safe, secure, self-confident, respected by allies and enemies, prosperous, and free. McKinley’s America was only a faint memory, a dying ember, and our enemies wished to stamp it out forever— but Donald Trump took that ember and built a campfire in 2015. Nearly a decade later, through mixed prosperity and suffering, that campfire is a bonfire, and the promise of a restored America seems within our grasp. If we are to reach out and grab it, however, Donald Trump must become the symbol of America. If he looks to the model Presidency, life, and person of William McKinley; then he just might do it. Our America is not yet gone.

And it’s gonna be great again.

William McKinley’s First Inaugural Address, 1897: https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/inaugural-address-43

William McKinley’s Second Inaugural Address, 1901: https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/inaugural-address-44

“William McKinley and His America,” by H Wayne Morgan

The title of the 21st Chapter of Morgan’s book— I thought it an apt description.

Morgan, p. 177

Morgan, p. 221

Morgan

James 3:1 ESV

Coming back to this article immediately after hearing Trump reference William McKinley's use of tariffs in his podcast sitdown with Dave Ramsey!

I heard you on JB show and was looking forward to this article and it didn't disappoint. Always good to learn about important history that gets overlooked